blog

Blog

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

14 Apr, 2023

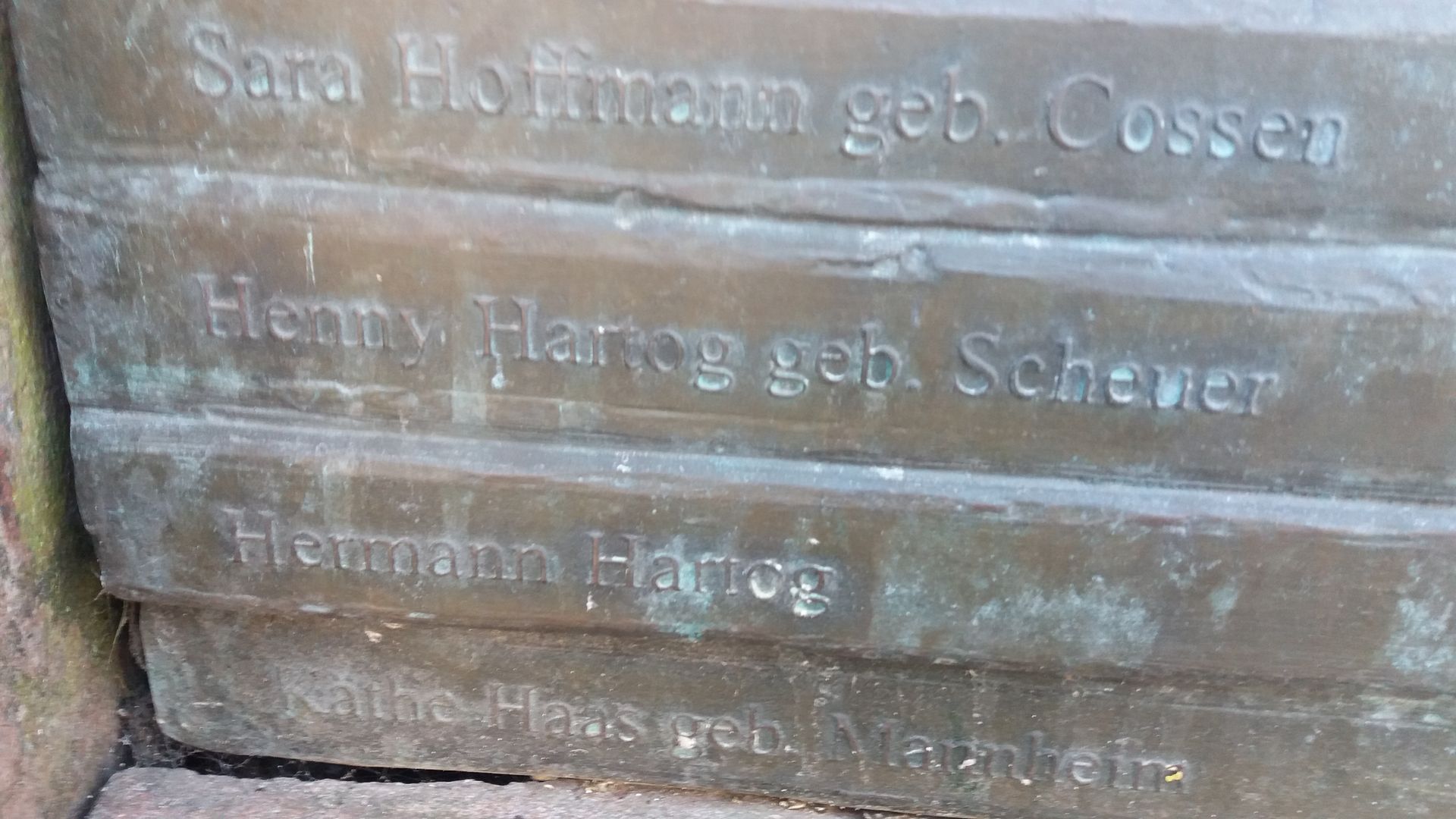

It is always very special to be going to Jever – a town in north-west Germany where members of our family lived and worked almost a hundred years ago. It is an event to anticipate with pleasure, to be grateful for the opportunities to reclaim an uncertain past, to meet with fellow travellers on a similar quest for an elusive but fundamentally necessary understanding of those who walked before us in Jever, who walked through our own lives, and who continue to walk with their descendants. We are the guests of those in Jever who keep alive the memory of the Jewish community that was once such a vital part of the town. It is a memory that almost disappeared without trace – at least, that was the plan of the ruling Nazi party during the 1930s in Germany. Certainly, their plan was successful in destroying millions of lives, in dispersing surviving German-Jewish families throughout the world, and in wiping out the culture and heritage of a significant group within German society. But the memory could not be totally annihilated. During the 1960s and 1970s, young people asked questions - and wanted answers: 'Who were the Jewish people in our society?' 'Where had they lived?' 'Why was there discrimination against them?' 'What did you do to help them?' The questions were difficult and troubling, and the answers were often evasive. But the students had teachers and leaders in the community who encouraged their curiosity, supported their tenacity, and enabled their research. As we approach our visit to Jever, we are the beneficiaries of those large-hearted people who are welcoming back the descendants of a once-vibrant force within the locality. We come from many parts of the world – all those places where Jews managed to get a visa for immigration; Israel, USA, Britain, Argentina, South Africa. It is good to greet each other, and to recognise our belonging. (photo shows the names of Henny and Hermann Hartog on the memorial in Jever)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

07 Apr, 2023

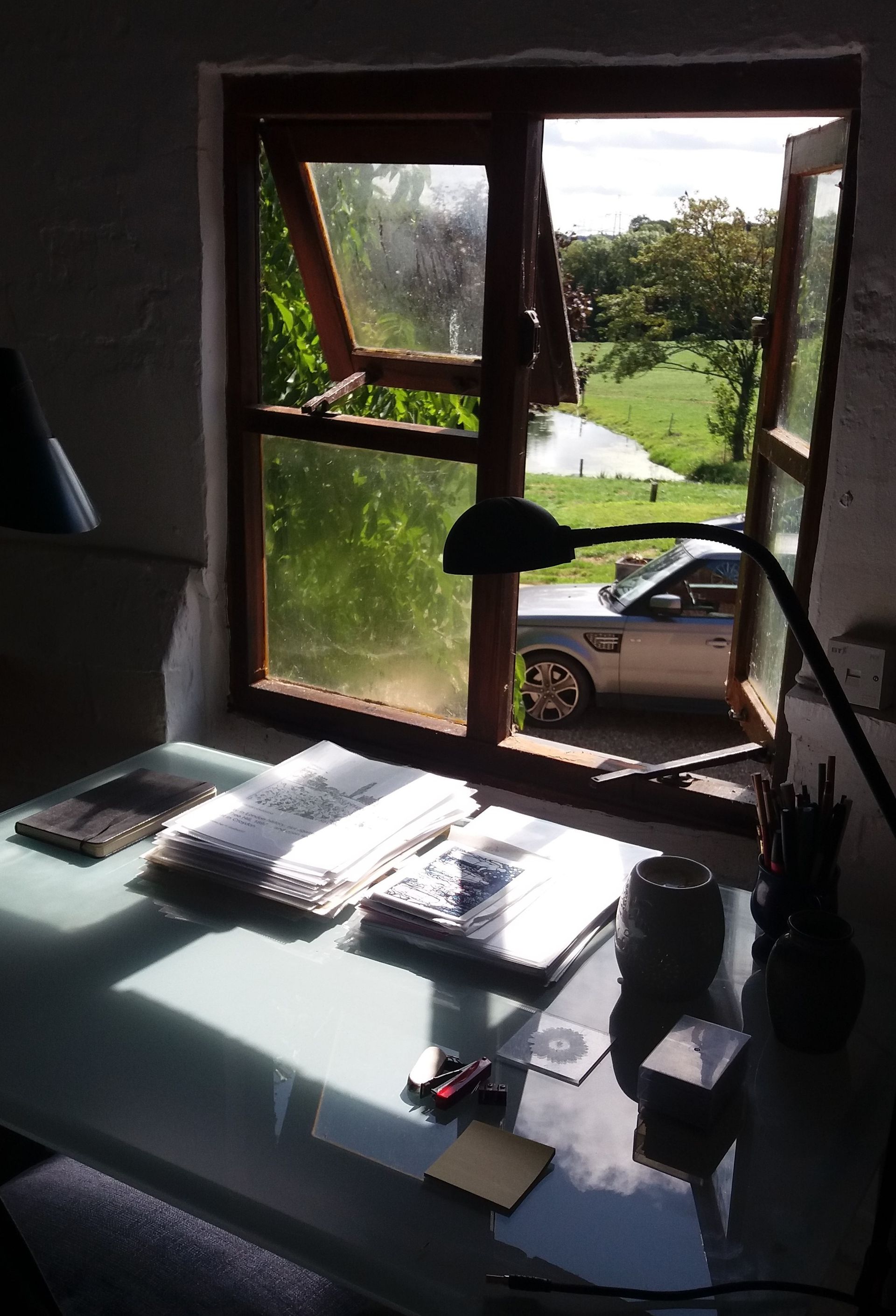

I like to know where writers write. Details fascinate me – the mess, or lack of it; the creative details, or their absence; the layout of desk versus window versus brick wall. So where do I write? For many years I worked from home and was happy to flit between the computer, washing machine, and school run. Sometimes I had more space than at others. The children left home, we downsized, and a small bedroom became my work space. Then the grandchildren arrived and very soon my writing room was taken over by a cot. Important documents fought with the needs of an infant. I took myself out of the house and found the ideal writing space. I now drive for an hour into the countryside - wonderful 'thinking time'. When I come to my destination I arrive at silence, except for birdsong. Crossing the courtyard, I let myself into an oast house and climb the steep stairs to my circular first floor room. It is usually freezing. My desk is in front of a window that looks out over the Sussex countryside. From time to time cars, farm vehicles and the postman scrunch over the gravel outside. Small birds flit around outside and nest in the eaves. On windy days the cowl on the roof thumps in time to my tapping on the laptop. The round walls are hung with images – collages of family photos, paintings by my grandchildren, treasured pictures. Surrounded by the people who matter to me, I write about what matters to me too. (photo shows the view from the window above my desk in my oast house writing room)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

24 Mar, 2023

For the past twenty years, my research has been subject to an avalanche of generosity. For example, when I first visited Potsdam in the footsteps of Herbert Sulzbach, I was at the end of a research trip and had limited time. The little information that I had proved to be unreliable but a young receptionist at Babelsberg Palace rushed to consult colleagues. Soon I was with the Potsdam librarian who gave me her time, advice and some contacts. Back home, I sent emails but little happened. Then came one lengthy reply, plus pictures. A kind historian had spent the weekend travelling to photograph exactly what I needed and writing a wonderfully detailed account. A year later, I was sharing coffee and cake with him and his wife in their home, and listening to even more insightful and helpful explanations. I wrote a letter to an ex-PoW who had known Sulzbach. He phoned back within days and a fortnight later I was driving to stay with him and his family to see his papers, and listen to his stories. Sons and daughters of ex-PoW have been amazingly generous with their treasured documents. 'I know it's in good hands', said one such son on our first meeting, dropping a massive file and photograph album on to the table. 'Just bring it back when you've finished with it', as though I dropped by Bonn from Brighton every few days. Before I started, I began a list of the complete strangers who have helped me to discover Herbert Sulzbach. It is far too long to print. In Featherstone Park camp, the prisoners used to speak of 'the Sulzbach spirit'. Perhaps it is this which has been following me around. (photo: Helga and Dr Klaus Arlt, Potsdam – with many thanks)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

10 Mar, 2023

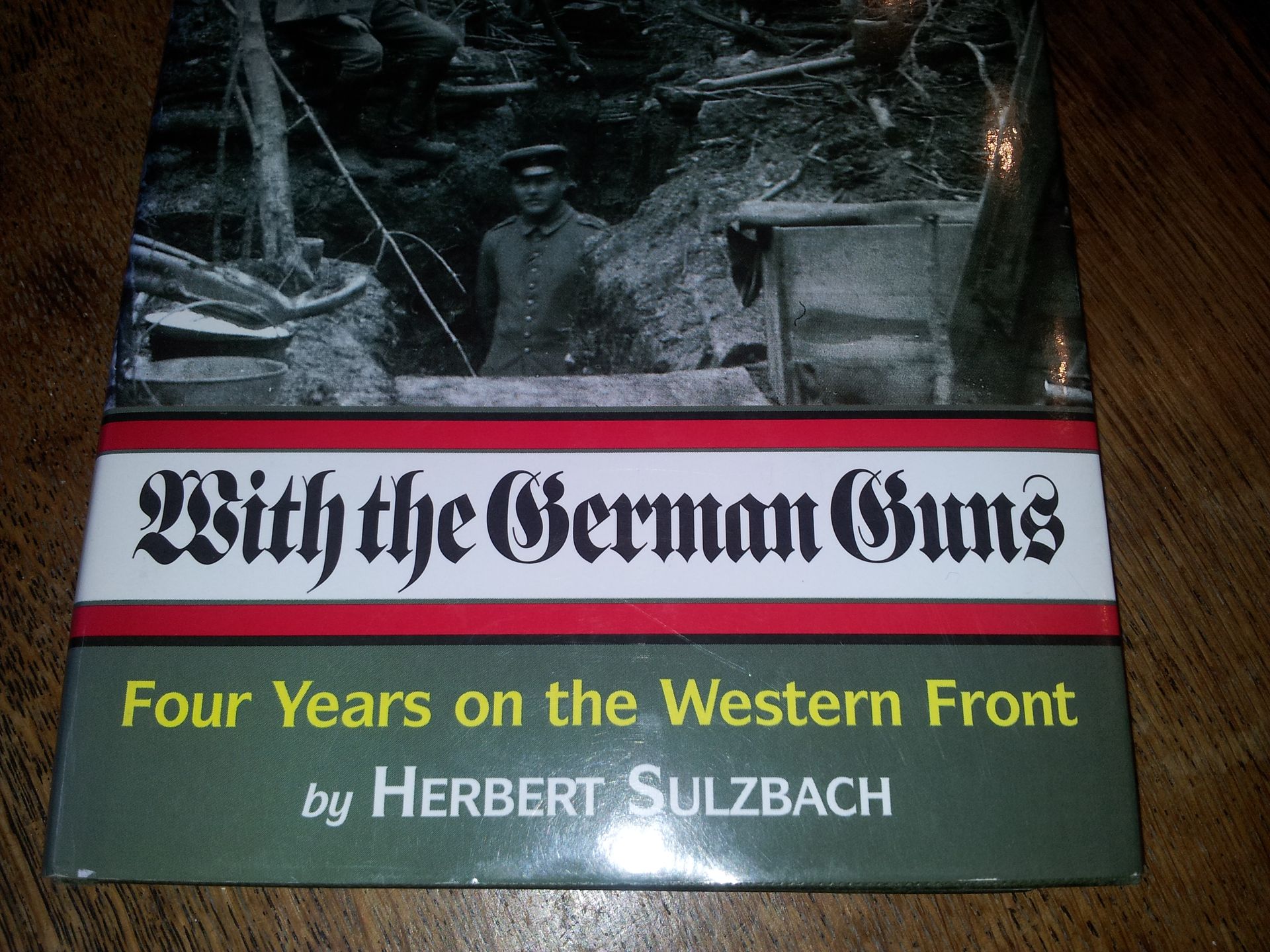

Herbert Sulzbach survived four years with the German army during the First World War. Throughout this time, he sent his diaries and photos for safe-keeping to his family in Frankfurt. Twenty years later, in 1935, he had them published in Berlin. ' Zwei lebende Mauern ' ('Two Living Walls') told of the ordeals and gallantry of German soldiers who showed courage, cheerfulness, and great patriotic pride. The book received high praise from the Nazi press, who presumably had not realised that Sulzbach was a Jew. Publication was two years after a massive book-burning in central Berlin of books written by 'degenerate' authors, and was just one year before Sulzbach was made bankrupt and forced into exile by the Nazis. Nazi endorsement for his book continued. As late as March 1945, a student leader of the Nazi Youth in Munich was issued with a copy which he was to read to his platoon at their weekly meetings. He had only got half-way through it when the American army arrived in Munich. The eleven year old was captured and his pack searched. When Sulzbach's book was discovered inside, the American lieutenant chucked it into the River Isar. Thirty years later, in July 1973, the diaries were translated and published as ' With the German Guns '. A complementary copy was – by chance - sent to the 'Hitler Youth platoon leader', who was by then living in England. He was delighted to carry on reading from where he had left off, and wrote to the publisher to say so. When Sulzbach heard, he invited the reader to be the guest speaker at his next Anglo-German Association meeting. ('With the German Guns' by Herbert Sulzbach is now published by Pen and Sword Books)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

23 Feb, 2023

'Die andere Seite' or 'Journey's End' 'Die andere Seite' ('The Other Side') opened on 29 August 1929 at a Max Reinhardt theatre in Berlin. The play, written as 'Journey's End' by Robert Cedric Sheriff, had already been staged in London and New York, and its premier in Berlin was enormously successful. Mathias Wieman acted in the main role of Stanhope, and the director was Heinz Hilpert. The setting of the play was the British front in WWI near St Quentin just before the German offensive in March 1918. Herbert Sulzbach, living in Berlin in 1929, went to see it at the Künstlertheater. In March 1918 he had fought 'on the other side' in that battle, and the play affected him deeply. 'Once, for a whole week long, I had behaved like that. Sheriff’s drama was set exactly at the same time as I, a young Prussian Lieutenant, and my regiment began the huge offensive early in the morning against the British 5 th Army. I lived through those great, terrible, and unbelievable days all over again.' Nearly twenty years after seeing the play, and after a Second World War, Captain Herbert Sulzbach arrived as an interpreter at a Prisoner of War camp for four thousand German officers at Featherstone Park in Northumberland. The cultural programme meant that the large camp had four theatre stages, and many of the prisoners took part in the dramatics. On 26 February 1946, one month after his arrival, Sulzbach was invited to a performance of 'Journey's End'. 'They put it on ten times, so that two thousand PoW could see the piece which I had once seen in 1929 in Berlin, where it had moved me enormously. Now I saw 'Die andere Seite' afresh from the other side, and as a British captain, myself in khaki, I watched German PoW playing British roles. It is too much to be able to take in! I went back to my hut deeply impressed.' (photo: the site of Featherstone Park PoW camp today)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

29 Aug, 2022

The 4 September is a memorable date for my husband and me; it is our wedding anniversary. But what we didn't know when we married on that gloriously happy and sunny day in 1971, was that about thirty years previously it had been a desperately sad and tragic day for our family. Not even my future mother-in-law knew the details: now, we do. On Friday 4 September 1942, eighty years ago this year (2022), my husband's grandparents were herded on to a cattle truck at the concentration camp at Drancy, in Paris. (It happened to be the Jewish Sabbath.) They were sent with other Jews on Convoy 28 from Drancy to the extermination camp at Auschwitz, where they were immediately murdered. Henny Hartog was 45 years old, and her husband, Hermann – a school teacher and cantor – was ten years older. Their daughters, then aged 17 and 15, were in England. There had been French people who had willingly tried to help, but ultimately they were unable to resist the arrest and deportation of the Jewish refugees from Germany who had lodged in their village in the foothills of the Pyrenees. Despite the courageous actions of their neighbours, Henny and Hermann had been rounded up by the French police who - acting on orders of those subservient to their German invaders - had returned them to the local concentration camp, Camp de Gurs. From there they had been transported by lorry to the nearby railway station, Oloron Sainte Marie, and then by cattle trucks to Paris. Henny and Hermann had been fearful of this outcome for some months. They had been able to listen to the radio reports over the summer months which described the rounding up of Jews in the south-west of France, for deportation 'to the east'. It was really just a matter of time before they, too, heard the knock on the door. There was little – at this stage – that their French friends could do for them, but they took care of some money, letters from the children, Hermann's religious vestments. In Camp de Gurs, there was not much time to make arrangements, but Henny gave another detained Jewish woman her daughter's address, and asked her to write: 'She asked me to write to you before she left. She looked well, she was very quiet (so was your father – and both were very courageous) and not afraid of the long journey. Your parents asked me to tell you that you must not be afraid, and not be worried if you hear nothing for a long time.' This year, we remember the thousands of Jewish people who were deported from the Unoccupied Zone of France to the extermination camps of Germany, eighty years ago.

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

13 Apr, 2022

Theirs was a forced emigration, and they planned carefully. However, circumstances changed all the while as they tried to make arrangements, and so plans were constantly having to be altered. It was only after the pogroms of November 1938 that Henny and Hermann Hartog had finally had to accept that they could no longer stay in Germany – but opportunities for emigrating were closing swiftly everywhere. By early 1939, they were trying to travel to relatives in America – to be joined there later by their two daughters in England – but waiting lists were lengthening rapidly. Their plan changed to find a way to emigrate to England, but there were huge obstacles to entry. Meanwhile, Henny arranged for many of their belongings to be taken in a container to the port in Bremen ready for shipping, but before long the costs of freight became so high, and money became so scarce, that they realised that this was probably not achievable. They left the 'Jew house' to which they had been allocated in Wilhelmshaven and went to live with Hermann's relatives in Aurich. Henny's father was already there; six adults in a not very large house. In April 1938, Henny travelled to Frankfurt to say goodbye to her elderly relatives. She enjoyed the journey and the fine weather, and was pleased to see hills and forests again after the flat moorlands of the north of the country. The old people were thinner and frailer than she remembered them, and she worked hard to make life easier for them. She made a detour as she returned to Aurich in order to say goodbye to Hermann's sister who lived in Cologne. In Frankfurt, she had also been preparing a place for her elderly father to live with his brother-in-law. Adolph Scheuer left Aurich for Frankfurt in May 1939, having made his home with Henny and Hermann for the previous nine years. Friends and neighbours in Aurich were all leaving if they could, although many of the young people had already gone. The Jewish teacher, Max Moses, left for Hamburg and the USA, and Hermann took his place teaching the few children who remained. All plans were hurriedly shelved when war broke out in September 1939, and a few weeks later Hermann arrived in Brussels to find a place where Henny could join him. She managed to get there in November 1939. At that time, they had little idea that their farewells to relatives and friends had been final. They had become refugees. (the photo shows Henny's father, Adolph Scheuer, in 1938)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

01 Apr, 2022

Men who served as combatants in both world wars very often recognised that they were fighting for a very different cause the second time round. In 1914 the British diplomat Harold Nicolson was 'burning for war'. Herbert Sulzbach felt much the same – as he volunteered for the German Imperial army. When he was elderly, Sulzbach wrote 'the Great War is still so near to us, nearer than 1939 – 45.' He often spoke of it as 'the 'last knightly war', when soldiers on both sides believed in the justice of their cause, were filled with idealism, and 'had respect of each other, in spite of the terrible fighting.' The artist Keith Vaughan, who was too young to fight in the First World War, distrusted such values. Painting scenes of barrack rooms in the Pioneer Corps – in places very similar to those in Sulzbach's Second World War service career - he considered that in wartime, 'it is through conditions commonly shared that one imagines oneself at one with [others], but it is an illusion.’ In his January 1932 diary, Nicolson described Hitlerism as 'a doctrine of despair' and foresaw a catastrophe for Germany. For the Jewish artist Samuel Bak, Nazism was 'a machinery of dehumanisation' where he realised 'what man is capable of doing to man.' Sulzbach fought Nazism, but not the 'other' Germany that he still believed existed. Despite the horrors, loss, and exile of the Second World War, Sulzbach held on to his chivalrous ideals. Wearing first field-grey for Germany and later khaki for Britain were both important. As a British officer, Sulzbach worked as an interpreter amongst German officer PoWs. Some of them shared his First World War experiences, and of one of them Sulzbach wrote, 'tomorrow General Heim will have been here for one year. I sent him a photo of me. “My comrade from 1914/18, my enemy from 1939/45, my friend since 20 May 46”'. (photo: military cemetery in Thiescourt, France, with German and Entente graves)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

07 Mar, 2022

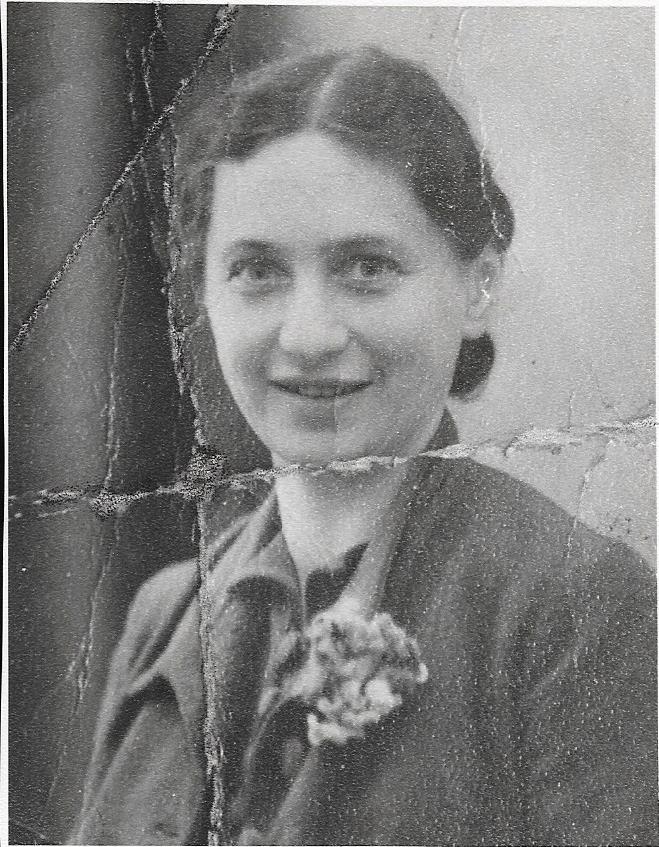

Henny Hartog was 40 years old when this photo was taken in 1937. She was a Jewish woman, married to a Jewish teacher – Hermann - and they lived with their two daughters in north-west Germany, in Wilhelmshaven. The previous year they had all waved goodbye to the elder girl, Lore, as she left for England to pursue an education that was no longer available to her as a Jewish youngster in Germany. One year after this photograph, on the night of 9/10 November 1938, Nazis burnt synagogues to the ground, destroyed Jewish businesses, and took Jewish people into custody, where they harassed and humiliated them. Henny and Hermann were taken into custody along with their younger daughter, Inge, and Henny's father. The following morning Hermann was taken to a concentration camp and the others were allowed home. Henny remained extraordinarily strong, despite 'wanting to cry my eyes out'. She arranged for her elderly father to go and live with Hermann's relatives away from the city, and immediately wrote to Lore with instructions of how to help their situation from England. Lore was 14 years old. Henny's other concerns were how to help effect Hermann's release, and how to get Inge to safety. Within the following week, the British government agreed to permit the temporary admission of Jewish children under seventeen years of age without their parents, and without the requirement of a visa. This transportation of children became known as the 'Kindertransport'. Clearly, not all children whose parents wanted them to go to England would be able to do so; Henny worked fast to secure a place for her younger daughter. She needed to complete a questionnaire concerning Inge's character and background, and enclose a photograph of her that were sent to the local social worker’s office. This office then sent the documents to the 'Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland' [the Federal Representation of Jews in Germany] in Berlin, together with Inge's health certificate - in order to receive permission to leave the country. Henny also had to sign a statement allowing the committee in Britain to look after Inge, and another statement that declared the religion that Inge had been brought up in. The documentation was then sent to London for review by the Refugee Children’s Movement. All went well, and Henny was issued with a travel date and departure details for Inge, who was allowed to take a small sealed suitcase with her – but no valuables, and only ten marks in money. She was included, with almost 200 other children, on the first 'Kindertransport' train which left the German town of Bad Bentheim, on the border of Holland, on Thursday 1 December 1938. Inge was then three days short of her twelfth birthday. (the picture shows Henny Hartog (born Scheuer) in 1937)

By Ainslie Hepburn

•

07 Mar, 2022

August 1914 was a month to remember for 20 year old Herbert Sulzbach in Frankfurt. On 2 August, Germany mobilised for war and there was 'magnificent enthusiasm and a superb mood'. His brother-in-law, a medical officer, reported for service on 3 August. Sulzbach himself volunteered with the local artillery and reported for duty on the 8 th – with many of his school friends. One of his girl friends gave him a lucky penny. There was 'much enthusiasm and tears'. An eleven o'clock curfew for the town surprised him and he was sad, but patriotic, when their much-loved Adler car was requisitioned and sent to the Front at Metz. Sulzbach's brother, Ernst, was in London and needed time to return home. A welcome telegram from Hamburg brought news from him, and he arrived in Frankfurt on 9 August. The following day Sulzbach was fitted with his uniform and had his photo taken with his girl friend. He felt strange as he walked around town, since he couldn't even salute. Three weeks later he was excited about his departure for the Front. On the evening of his farewell, 29 August, news arrived that his brother-in-law's ship had been sunk and his sister's husband was dead. She could barely face her brother to wish him goodbye. In another August, many years later, Sulzbach stood in the half-destroyed centre of Frankfurt and told a companion how he had once walked around town unable to salute. He also described how a horse – on which sat a young Lieutenant - had come through, leading the forage wagons. He knew the name of the Lieutenant, Fränzchen Trier. A few minutes later Sulzbach and his companion were in a restaurant. He was fascinated by an older man and asked the waiter if he knew the man's name. 'Yes, that's Cavalry Captain Trier'. This was 1950. Thirty six years and two World Wars had since passed. (the picture shows leafy Friedrichstrasse in Frankfurt where Sulzbach lived in 1914)